Social Darwinism in the United States

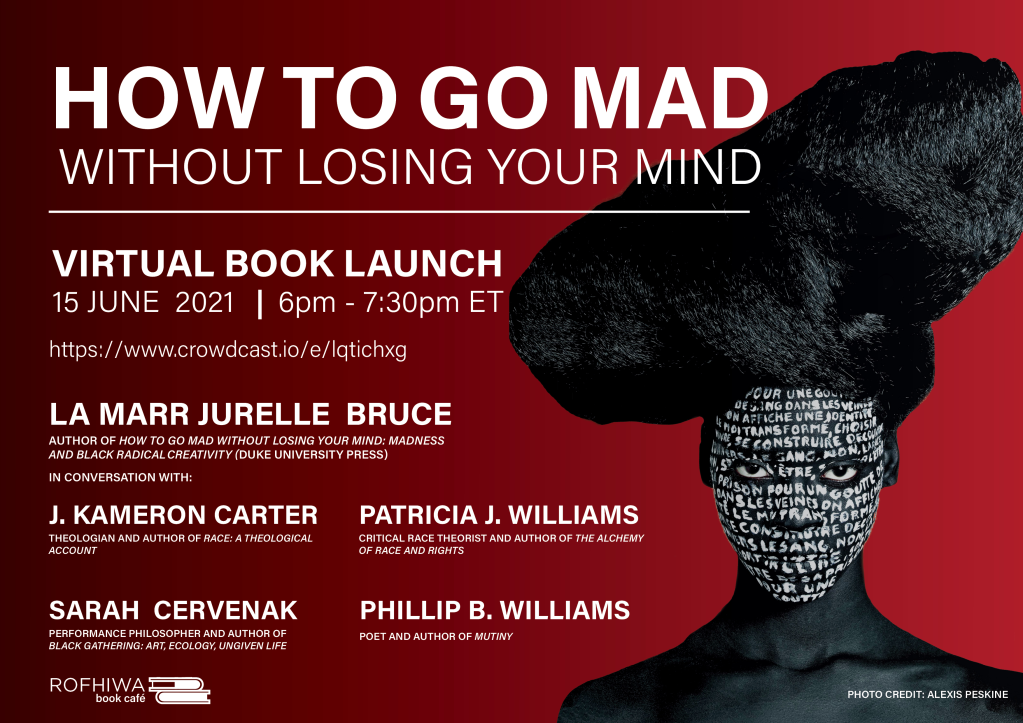

By Patricia J. Williams Times Literary Supplement, August 6, 2021, https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/facing-reality-charles-murray-book-review-patricia-j-williams/

A Eugenics Society exhibit, c.1930|© Wellcome LibraryAugust 6, 2021Read this issue

A Eugenics Society exhibit, c.1930|© Wellcome LibraryAugust 6, 2021Read this issue

IN THIS REVIEW

FACING REALITYTwo truths about race in America

168pp. Encounter Books. $25.99.Charles MurrayLong reads

In 1853, Joseph-Arthur, Comte de Gobineau published a tract entitled “Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races”, in which he argued that “history springs only from contact with the white races” and that miscegenation with “commoners” as well as with “yellow” and “black” races leads to the “demise of civilization”. Widely credited with popularizing the concept of the Aryan master race, Gobineau’s thoughts found purchase among pro-slavery Americans and, eventually, became an ideological cornerstone for the American Breeder’s Association, the American Eugenics Society and the Nazi party. His royalist assertions of elite white “bloodlines” have been enduringly influential in the United States.

Few have had a greater hand in carrying Gobineau’s notions into the present than Charles Murray. Along with J. Philippe Rushton, Arthur Jensen, Richard Herrnstein and Nicholas Wade, Murray has championed social Darwinism, an ideology that divides humans into biologically distinct “races” with distinct genetic propensities that neatly predict everything from penis size to brain function and criminal disposition. Their bottom line is that dark-skinned people are evolutionarily limited and thus unsuited to modern life.

Hard scientific evidence contradicts the narrative. Yet the reason I find myself writing this review in 2021 is that lots of people still believe it, want to believe it, and remain committed to the disparagements such colonial conceptions invite. Little for them has changed since Gobineau’s day, and since the Victorian Francis Galton, who invented the word “eugenics” in the late 1880s, postulated that “there exists a sentiment, for the most part quite unreasonable, against the gradual extinction of an inferior race”.

The Bell Curve: Intelligence and class structure in American life, co-authored by Murray and Herrnstein, ignited an infamously bitter round of the so-called culture wars when it first appeared in 1994. While Herrnstein died shortly after publication, Murray continued to carry the torch, despite his theories being repeatedly debunked. (The most well-known refutation is probably Stephen Jay Gould’s The Mismeasure of Man, 1996.) Still Murray rises, every few years a new book, a new version of the same old narrative. He is a potent pundit whose convictions are spread gleefully by the Wall Street Journal and Fox News.

But Murray’s latest rehash, Facing Reality: Two truths about race in America, drops into the conversation at a particularly flammable moment. In brief, the American “reality” Murray presents is a construct of “race” as a category of unyielding genetic difference, a sealed box of capability, disposition and destiny. The first “truth” he abstracts from the box is that “American Whites, Blacks, Latinos, and Asians, as groups, have different means and distributions of cognitive ability”. The second “truth” is that “American Whites, Blacks, Latinos, and Asians, as groups, have different rates of violent crime”. Murray claims that “the numbers show” that those of African descent are biologically less intelligent than whites and more prone to violence. “The numbers show”, he insists, that such predispositions are unaffected to any significant degree by environment or nurture. Thus, he argues, it is a waste of time and money to be concerned by racial disparities in our societies, because unequal social outcomes are attributable to immutable difference.

Murray’s work is not really about biology and does not withstand scrutiny as such. His adventure began as an attack on the post-civil-rights era remedy of what he calls “aggressive affirmative action” in the US and his persistent aim has been to devalue the inclusion of African Americans in mainstream American society, whether in higher education, the professions or government service. His ideas have also been underwritten and promoted by right-wing and ultra-libertarian foundations such as the Manhattan Institute, the American Enterprise Institute and the Hoover Institution, which generally advocate shrinking all public spending, including in education. But Murray is not largely concerned with belt-tightening. He is specifically intent on proving differences between those received as white in American society and those perceived to be Black. In some of his books, he ranks Jews, women and “model minorities” as well, but there is always a singular drumbeat: that African Americans suffer from mental deficiencies that simply can’t be fixed. Be nice on an individual basis, he says, but collectively “they” are “different”. Moreover, Murray’s analyses do not merely presuppose white superiority and Black inferiority as standalones: the two are positioned in zero-sum relation to each other.

When I was first asked to write this review, I declined. I was reminded of Bertrand Russell’s eloquent response to an invitation to debate Oswald Mosley, the founder of the British Union of Fascists:

It is not that I take exception to the general points made by you but that every ounce of my energy has been devoted to an active opposition to cruel bigotry, compulsive violence, and the sadistic persecution which has characterized the philosophy and practice of fascism. I feel obliged to say that the emotional universes we inhabit are so distinct, and in deepest ways opposed, that nothing fruitful or sincere could ever emerge from association between us … It is not out of any attempt to be rude that I say this but because of all that I value in human experience and human achievement.

I thought, too, of the Princeton genomics professor David Botstein’s denunciation of The Bell Curve as “so stupid that it is not rebuttable”. To decline seemed the better path to sanity.

My mind was changed by the florescence, especially after January’s attack on the Capitol, of references to “fear of white replacement”. The idea, a favourite of the ultra-right, has re-entered the mainstream, as expressed by Republican members of Congress, such as Representatives Marjorie Taylor Greene and Scott Perry, and by popular television pundits including Tucker Carlson; it has been used to justify border walls and cages for migrants, as well as hate crimes and mass shootings. While the demographics of the US are indeed changing – forty years from now, those who are thought of as white today may be outnumbered by those who are thought not to be – we have been here before. In the first half of the twentieth century, “White Anglo-Saxons” felt at risk of being outnumbered by Italian, Greek, Armenian, Jewish, Russian, Latvian, Estonian and other Eastern European immigrants, who were not considered “white”. Then too people spoke of a “crisis”. But the siege mentality has taken a decidedly dark turn of late, focused on minority voters, imagined hordes of unsavoury “critical race theorists”, migrants and refugees. It has been accorded increased volume by some combination of the ungoverned corners of the internet, pandemic derangement, profound economic anxiety, and a renewed fascination with notions of genetic “purity”, the latter fuelled in no small part by the marketing of home DNA testing kits which translate the tens of thousands of haplotype groups and infinitely varied markers of human diaspora into reductive “percentages” of purported racialized heritage. (Dorothy Roberts’s Fatal Invention: How science, politics, and big business re-create race in the twenty-first century, 2012, is particularly good on this.)

I decided to write the review because today the US is close to a kind of free enterprise civil war in which the very definition of criminality has been raced, as in the casually reiterated defamation that “blacks commit all the crimes”. This assertion often contrasts with wild rationalizations about a broad range of white criminality. According to a recent Reuters poll, for example, nearly half of Republicans believe that the attack on the Capitol was “largely a non-violent protest or the handiwork of left-wing activists ‘trying to make Trump look bad’”. Although she was later censured, Virginia State Senator Amanda Chase described the people who stormed the Capitol – and who beat and injured at least 140 police officers, defecated in the halls, broke into offices and stole files and computers – as “patriots”. While conceding “some acts of vandalism”, Representative Andrew Clyde minimized the siege which cost five people their lives: “You know, if you didn’t know the TV footage was from January the 6th, you would actually think it was a normal tourist visit”.

My goal here is not to attempt yet another refutation of Murray’s theories. (For that, there’s Troy Duster’s Backdoor to Eugenics, 2003; as well as Harriet Washington’s A Terrible Thing to Waste: Environmental racism and its assault on the American mind, 2019.) Instead, I will point out the most dangerous bits of Murray’s political agenda, while providing more grounded bibliographical sources – before they disappear, given the sudden proliferation of state laws suppressing the teaching of anti-racism or other “controversial” topics. Since January this year, twenty-nine states have proposed bills to restrict or ban such teaching; nine have enacted legislation to that effect.

Murray starts with what he styles as “the struggle for America’s soul”. “You have to be quite old to remember how uncomplicated it seemed to many of us, White and Black, in 1963”, he says, wistfully. With the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, “We had done it. We had set things right … The act had to be a good and necessary thing. As a college junior at the time, I certainly thought so.”

I was not yet a teenager in 1963, a year that spanned the Alabama Governor George Wallace’s “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever” speech, Martin Luther King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”, Bull Connor’s deployment of firehoses and police dogs against civil rights protesters, and the assassination of JFK. No sentient being could have thought things “uncomplicated”. In a rhetorical tic, Murray resorts to such nostalgic tropes to sprinkle fairy dust on his arguments. His use of the past tense, the insistently well-intentioned “I used to think”, signals an older-wiser tone of innocence betrayed, difficult “truths” revealed, and the regrettable “reality” that “we have kidded ourselves that the differences are temporary and can be made to go away”. This pure-hearted stance underwrites crocodile tears about how much it pains Murray to become a warrior of unpleasant revelation; it takes “courage” and “bravery” to stand firm, even if you get called “a racist and hateful person”. Don’t be afraid, he instructs “us”, to say that vast racial disparities in American society exist because they should. They are what they are because it is what it is.

This “is-ness” allows Murray to assert “group difference” without ever interrogating how such group identities came to be formulated and normalized, specifically in the American context. If population data sorted as “White”, “Black”, “Asian”, or “Latino” is “naturalized” as genetic, we obscure the imprint of policy decisions that created such demographic lumps to begin with: including anti-miscegenation statutes, anti-literacy laws, the history of homesteading in creating raced geographies of wealth, the legacies of financial red-lining and legally enforced housing segregation, economic migration, moral panics about ethnicity and resistance to linguistic diversity. These are complications worthy of studied consideration. Since you won’t find mention of them in Facing Reality, I recommend a dive into deep history with Charles Mann’s 1491: New revelations of the Americas before Columbus (2005); Forget the Alamo: The rise and fall of an American myth, published earlier this year by Bryan Burrough et al; Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States (2015); Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America (2018); Bill Ong Hing’s Making and Remaking Asian America through Immigration Policy, 1850–1990(1994); Richard R. W. Brooks and Carol Rose’s Saving the Neighborhood: Racially restrictive covenants, law, and social norms(2013); and Mitchell Duneier’s Ghetto: The invention of a place, the history of an idea (2016).

Murray does not seriously consider the disruptive stresses of racially segregated communities living on top of toxic waste dumps, or evicted multitudes trying to subsist on the streets; he doesn’t address stop-and-frisk policies directed at some but not all. (See Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow, 2013; and Eugene Jarecki’s documentary film of 2012, The House I Live In.) He does not consider vast racial disparities in government responses to the devastation of Hurricane Katrina; or to man-made catastrophes such as that befalling Flint, Michigan, where the entire population (more than half of which is Black) was poisoned by a lead-contaminated water supply imposed on it by a Republican governor interested in “cost-cutting”. (For documentation of how lead poisoning irreparably damages children’s brains, read Gerald Markowitz and David Rosner’s Lead Wars: The politics of science and the fate of America’s children, 2013; and Rob Nixon’s Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, 2013.)

Murray certainly does not consider the educational limitations of racially segregated life in the US: who has access to advanced placement classes (where some high school students are taught college-level curricula), who has science labs or foreign- language classes, school nurses or guidance counsellors; who as a kindergartener is likely to be sent to the police rather than to sit in the corner and to be expelled before the age of ten; whose school has more police patrolling the halls than books in the library. This parallel “reality” is ignored.

Under slavery it was illegal to teach slaves to read. Under Jim Crow, Black students were legally segregated with little access to public resources. Under today’s “colour-blind” regimes, de facto segregation is frequently enforced by ostensibly “race-neutral” laws against “boundary-hopping” between school districts. One of the saddest uses of the legal system in our post-civil rights era is in cases where poor, almost always Black, parents are sued or jailed for lying about their address in order to send their child to a well-resourced school in a better (almost always whiter) neighbourhood. The charge is called “theft of education”. Consider the case of Kelley Williams-Bolar, who used her father’s address in a nearby suburb to move her children from a dilapidated school in Akron that met only four of Ohio’s educational standards to one that exceeded all twenty-six of the guidelines. The school hired investigators and found that the children were living with their grandfather only five days a week, returning to their mother on weekends. In 2011, Williams-Bolar and her father were charged with felonies: falsification of records and theft of public education. She was given two five-year jail terms, suspended; she ended up serving nine days in jail, plus three years of probation and eighty hours of community service.

Without a nod to social history of this or any other sort, Murray skips to human assortment. Claiming to seek more “clarifying”, “dispassionate” nomenclature that will do away with unintended “semantic baggage”, to make it “easier to look at some inflammatory issues with at least a little more detachment”, he declares: “I substitute European for White, African for Black, Latin for Latino, and Amerindian for Native American. Asian remains Asian”. This trick of labels allows Murray to ignore slavery’s inheritance, leap over any question of epigenetics, nurture or environment, and generalize his convictions into the imagined form of biologically segmented humanity. (To understand how inheritance laws of hypo-and hyperdescent affected perceptions of who is related to whom in the breeding system of racial property, see Jennifer Morgan’s Reckoning with Slavery: Gender, kinship and capitalism in the early black Atlantic, 2021; and Ariela Gross, What Blood Won’t Tell: A history of race on trial in America, 2008.) And, at first, Murray is coy: “There is something intuitively wrong about calling American Whites Europeans when American Whites are so clearly not like Europeans in Europe. The same is true of American Blacks compared to Africans living in Africa, American Latins living in the United States compared to Latins living in Latin America, and, for that matter, American Asians compared to Asians living in Asia”. But then he drives his larger point home: “Better that you be jarred, I decided, if it might improve my chances that you understand the sentence as I intend it to be understood”.

For the like-minded, Murray has laid a nice clear path. “I don’t ask for much … I will be gratified if researchers are buffered from accusations of racism because they entered IQ scores as an independent variable of regression analysis.” He simply wants “policy analysts to incorporate race differences into their analyses”. It follows: “don’t assume that successful reforms must raise test scores” of Black and Latino children. (He believes it can’t be done.) It follows: don’t trust the seemingly outstanding resumés of Black and Latino candidates. (Liberal schools belch out minorities of consistently inferior calibre, Murray says.) “If you are researching racial discrimination in the job market, recognize that controlling for educational attainment isn’t good enough … Control for IQ as well.” In assigning genetic causation to differences between the IQ scores of “Africans” (Black Americans) and “Europeans” (white Americans), Murray writes off the fact that racial gaps have narrowed considerably over the past few decades, in line with greater literacy, better education, better diet, better housing, better health. He takes issue with well-established findings, such as the “Flynn effect”, according to which IQ has been rising for all since the beginning of the twentieth century, in part because of fewer stressors including war, famine and infection. He ignores how culturally specific IQ tests are, yet also how ungoverned and methodologically incommensurable. (This incoherence is the topic of Aaron Panofsky’s detailed study, Misbehaving Science: Controversy and the development of behavior genetics, 2014.) He ignores the way that international comparisons unsettle some of his geneticized stereotypes. In 2010, for example, Israel’s national IQ, not including the West Bank, was lower than that of the state of Mississippi, and as of 2019, Mongolia’s was higher than Sweden’s. He ignores the fact that “European” Americans score lower than most Europeans in Europe. He does not consider that high-scoring China tests only a well-chosen 500,000 of its billion plus citizens, while the much smaller US tests 1.5 million. Finally, he dismisses the documented effects of early childhood enrichment programmes and scoffs at the disempowering effects of stigma.

Murray invokes data: “Africans, at 13 percent of the population accounted for only 3.6 percent of CEOs, 3.7 percent of physical scientists, 4.4 percent of civil engineers, 5.1 percent of physicians and 5.2 percent of lawyers”. But, contemplating these figures, “your inferences could be completely wrong” unless you take into account how much dumber Blacks are: in Murray’s opinion, the numbers showoverrepresentation because minorities only “get through” – he always uses the language of contaminants – the educational pipeline because of “preferential treatment”. Hence, there ought, really, to be fewer. (For more about how wrong, and politically subsidized, Murray’s manipulation of such data is, there is Angela Saini’s excellent Superior: The return of race science, 2020.)

This weighted presumption of white superiority reinscribes precisely the disparagement that affirmative action law was designed to overcome and re-legitimizes the knocking-off of points and opportunities for the historically disenfranchised. Murray declares that “race differences in cognitive ability and crime” should be a consequential part of policy decisions affecting “income inequality, efficacy of preschool and jobs programs, the causes of residential segregation, the voting behavior of the working class”. He casts any dissent as mere “identity politics”, distracting “us” from “warding off the jungle. It is the jungle, the primitive sense of ‘us against them’ pressing in on the garden”.

Lest there be any doubt about what Murray is vaunting, consider the recent lawsuit against the National Football League for damages suffered by players because of the NFL’s active denial and suppression of data linking concussion and long-term brain damage, including dementia. Because the lawsuit joined the claims of thousands of former players, the litigation resulted in a billion-dollar settlement. But, as recently reported by the Associated Press, distribution of the award has run into problems: the NFL “has insisted on using a scoring algorithm on the dementia testing that assumes Black men start with lower cognitive skills. They must therefore score much lower than whites to show enough mental decline to win an award”. The practice, overlooked until 2018, has rendered Black former players less likely to qualify for compensation. In May this year, a petition signed by more than 50,000 former players and supporters asked the court to make public the metrics by which payouts were being allocated. Most importantly, the petition demanded an end to the practice of “race norming”, a broad medical practice in America (and elsewhere), where some treatments continue to rely on uninterrogated, centuries-old assumptions. (For a dissection of one such myth, see Lundy Braun’s recent Breathing Race into the Machine: The surprising career of the spirometer, from plantation to genetics, which shows how beliefs about the superior lung capacity of white people have led to the automated “race correction” of pulmonary readings.)

Murray does not address the NFL’s scoring of attributed cognitive value and yet it conforms precisely to his idea of a good policy – one that makes race an “added, independent variable”. (Still, he denies that anything structural is at work.) If Blacks are simply genetically less intelligent, then the justice system’s slashing of the settlement awards is “fair” and “common sense” (words Murray adores).

Separate but unequal is Murray’s glib conclusion. Treat minorities “as though” they were equal, but “save the soul” of America by imposing policies that “recognize” their inequality as “immutably real”. The most painful circularity of Murray’s thought is that when “you” – the you of his address is always “European” – encounter a minority who is “equal”, or even more accomplished than you, you can rest assured of your superiority by reminding yourself that they are “exceptions” to the rule. A particularly capable minority specimen is posited as a separate kind of “equal”, marked by the abnormal superpower of having measured up to a “European” norm of intelligence and behaviour. While advocating that the reader “resist generalizing”, in the next breath he asks that you suppose yourself to be a “White” (by the last chapter he has reverted to “White” and “Black”) who is,

living in a multiracial working-class or middle-class neighborhood in a megalopolis. The great majority of crimes are committed by minorities. Most of the children in the bottom of the class in your child’s school are minorities. These observations are not the products of a racist imagination. They are the facts of your lived experience. There are exceptions to be sure – your daughter’s super-smart minority classmate, the minority couple down the street who provide loving care for foster children, the minority cop you watched deftly defuse an escalating confrontation. But your lived experience tells you that these are not typical. Is it OK for you to generalize that minorities are criminal and dumb? Obviously not. The obviously correct answer is that a difference in means exists, but that we must insist on treating people as individuals.

There are so many things wrong with this passage. For one thing, the US is still a majority white nation in which most crimes are committed by whites, even if there are disproportions in rates of who is arrested and convicted. But let’s begin with the frame: an invitation into a normative “White” brain imaginatively constructed as floating through a “typical” “lived” “multiracial” experience. The scene is, in fact, atypical for most white Americans. According to the Brookings Institute, the average white resident of metropolitan America lives in a neighbourhood that is 71 per cent white, 8 per cent Black, 12 per cent Latino or Hispanic, with a statistically unclear percentage of Asians and “others”. Even this is misleading when one takes into consideration the further lack of contact imposed by racial separations that are trackable block by block, job by job, school by school and building by building.

But Murray resents any suggestion that he has misapprehended things: “Blacks, constituting 13 percent of the population, are telling Whites, 60 percent of the population, that they are racist, bad people, the cause of Blacks’ problems, and they had better change their ways or else”. He casts as “victims” those journalists and academics who (like himself) have been criticized for racist or sexist commentary. To those mirrors of himself, he counsels “bravery” in resisting “woke culture” while warning that “new ideologies of the far left are akin to the Red Guards of Mao’s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution of the 1960s, and they are coming for all of us”. The culture wars into which we have all been co-opted are unwinnable when apostasy is at stake rather than good faith. As David Botstein warned, beliefs that are profoundly wrong yet widely held may add up to an “unrebuttable” stupidity.

So here we have it: a book, published in 2021 that could have been written in 1921, or 1821. A book that forces the reader to confront the basics of white supremacy and take a stand. Murray’s constructed “reality” poses a simple set of direct questions: do you believe not in the magnificent randomness and infinite mutability of human potential, but rather that our most significant variability is transmitted through melanin? Can you “naturalize” the histories of segregation, poverty and social trauma by reassuring yourself that such disparities are the rational fallout of inherent genetic defect? A moral crossroads is laid before the reader: a choice. But, writing this, I can change no minds. Walking into the conceptually gated community of Charles Murray’s “us”, “I” become “you people”.

Patricia J. Williams is the author of Giving a Damn: Racism, romance and Gone with the Wind, 2021